Evaluating the drivers of extreme runoff using satellite-derived river discharge estimates

Project Members

Mike Talbot, Frances Davenport

Study Areas

CONUS, Global

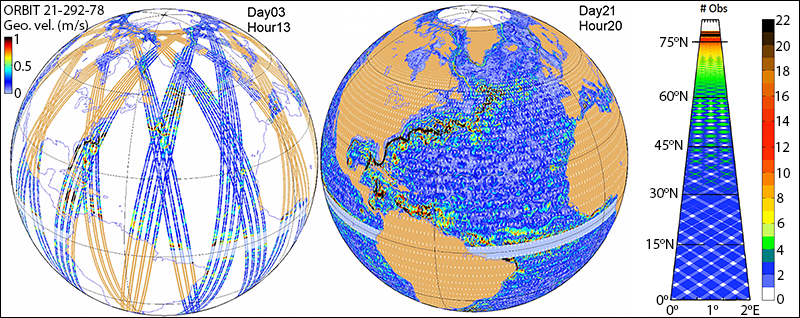

SWOT satellite orbit progression [source: JPL]

Overview

Droughts and floods are two of the most common and widespread natural disasters, each affecting more than 70 million people globally per year - more than any other natural hazard. While these hydroclimatic extremes have always posed challenges for society, climate change is now exacerbating the frequency and intensity of these events across the globe, and both wet and dry extreme events are very likely to get worse with additional global warming.

There remain significant uncertainties around hydroclimatic extremes and how they are changing on regional and local scales, which presents major obstacles for climate risk management and adaptation. Multiple challenges make it difficult to study and predict hydroclimatic extremes. One challenge is the lack of historical global-scale observations of variables like streamflow. Indeed, in large regions of the world, such as much of Africa, Central America, and Asia, the vast majority of streams remain ungauged. Without historical observations it is difficult, if not impossible, to quantitatively assess whether floods and streamflow droughts have been changing over time.

Global discharge observations from the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) mission present a new opportunity to understand hydroclimatic extremes at a global scale. In addition, a suite of emerging data-driven methods makes it increasingly possible to extract valuable insights from large hydrologic datasets. This project seeks to improve global-scale process understanding of the response of hydroclimatic extremes to changes in underlying hydroclimatic drivers by combining SWOT river discharge estimates with emerging data-driven approaches in hydrology.

How are hydroclimatic extremes responding to climate change?

Despite gaps in our understanding of how hydroclimatic extremes will respond to climate change, we have more confidence that many underlying hydroclimatic drivers are changing. For example, with increasing atmospheric temperature, the saturation vapor pressure of the atmosphere increases, leading to approximately a 7% increase in the moisture holding capacity of the atmosphere for every 1°C increase in atmospheric temperature. This can increase the availability of moisture during storm events, resulting in more intense extreme precipitation.

Changes in atmospheric evaporative demand (AED), influenced by higher temperatures, affect evapotranspiration, aridity, and the energy balance at the land surface. This can exacerbate drought conditions and increase stress on ecosystems. Additionally, drying at the land surface and decreases in soil moisture can modulate the effect of extreme precipitation on floods. Regions experiencing a shift from snowmelt to rainfall due to warmer winters may see increased flood risks, even without changes in precipitation amounts.

A key unanswered question in hydrologic science is how simultaneous, complex climate changes will collectively affect hydroclimatic extremes in different regions. Understanding these interactions is critical for improving climate risk management and adaptation strategies.

Can access to massive datasets improve our physical understanding of hydrology?

The integration of SWOT observations with advanced data-driven methods, such as machine learning and panel regression models, provides a unique opportunity to improve our understanding of hydrological processes. These methods allow for the analysis of large-scale hydrologic datasets, uncovering patterns and relationships that traditional models might miss. By leveraging these datasets, we can enhance our ability to predict and manage hydroclimatic extremes, ultimately contributing to more effective and informed water resource management and policy decisions.